- Home

- Jimenez, Stephanie

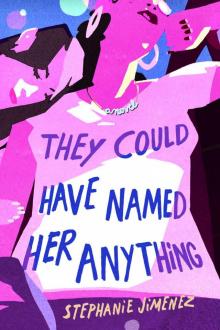

They Could Have Named Her Anything

They Could Have Named Her Anything Read online

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THEY COULD HAVE NAMED HER ANYTHING

“Stephanie Jimenez’s characters want to know, desperately, sincerely, where they might belong. In pursuit of this question, they cross borders and expectations—of class and race, of their roles as women, daughters, fathers, lovers—barreling through their mistakes with clear-eyed hope that it will pay off. They Could Have Named Her Anything is a powerful reminder that moving between worlds is rarely free, and that the most valuable educations take place outside the classroom.”

—Danielle Lazarin, author of Back Talk: Stories

“They Could Have Named Her Anything is a profound exploration of desire: the desire to fit in, the desire to understand ourselves, the desire to be accepted for exactly who we are. As our characters reckon with their own yearnings in a New York City full of dichotomies, this novel pulls us thrillingly between the Hamptons and Queens Boulevard, the private school system and working-class life. Stephanie Jimenez comes to her debut with rare insight and extraordinary empathy, bringing us characters so real they feel like family.”

—Danya Kukafka, author of Girl in Snow

“This gorgeous debut from Stephanie Jimenez brims with visceral details. They Could Have Named Her Anything captures all of the aggressive beauty and tension of growing up, the complexity of families, and what it’s like to come of age in a city among millions. I was immediately drawn in by Maria, Jimenez’s sharp and observant protagonist, and her vivid, urgent journey.”

—Natalka Burian, author of Welcome to the Slipstream and A Woman’s Drink

“They Could Have Named Her Anything is surprising, explosive, charged with suspense and drama as it travels from Queens to the Upper East Side to Las Vegas. And yet, it’s also contemplative and introspective, an intimate portrait of one young woman, stuck between secrets and lies, her responsibility to her family, and her own dreams. This book kept me guessing, intrigued, and revisiting my own adolescence, as I read to see how far Maria Rosario would go in her pursuit of her own life.”

—Naima Coster, author of Halsey Street, finalist for the 2018 Kirkus Prize

“Lyrical, sophisticated, and oh-so-real, They Could Have Named Her Anything will take your breath away. Full of powerful, no-nonsense girls who know what they want and who’ll do anything to get it, They Could Have Named Her Anything is a timely love letter to womanhood, the messiness of friendship, and the city of New York.”

—Ashley Woodfolk, author of The Beauty That Remains

“In They Could Have Named Her Anything, Stephanie Jimenez has constructed a beautiful, unflinching narrative about the time in one’s life when we go from being defined by what others think of us to unapologetically embracing our complicated and fluid selves.”

—Natalia Sylvester, author of Everyone Knows You Go Home and Chasing the Sun

“Stephanie Jimenez uses ultra-fine brushstrokes to paint a portrait of two families intertwined by fate and desire, wanting and becoming. With flawless eye for detail, we see just how differently the same city can look, even from the eyes of friends. Tightly drawn characters and beautifully woven plotting reveal the simple truth that coming of age for young women in the modern era is never simple at all. As Maria navigates a tightrope walk as a scholarship student from Queens in the world of elite private education, she learns the adult world is not what it seems and that bitter often comes with sweet. A haunting, unsparing tale of girlhood from an important new voice in literature.”

—Meghann Foye, author of Meternity

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2019 by Stephanie Jimenez

All rights reserved.

Excerpt from THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET. Copyright © 1984 by Sandra Cisneros. Published by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House, and in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf in 1994. By permission of Susan Bergholz Literary Services, New York, NY and Lamy, NM. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Little A, New York

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Little A are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781542003742 (hardcover)

ISBN-10: 1542003741 (hardcover)

ISBN-13: 9781542003759 (paperback)

ISBN-10: 154200375X (paperback)

Cover design by Faceout Studio, Spencer Fuller

Cover illustrated by Ronald Wimberly

First edition

For Xiomara Useche Jimenez, my closest friend

CONTENTS

START READING

QUEENS, NEW YORK

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

All you wanted, Sally, was to love and to love and to love and to love, and no one could call that crazy.

—The House on Mango Street, Sandra Cisneros

QUEENS, NEW YORK

MAY 2006

CHAPTER 1

In the Rosario household, where four people lived on the first floor of a two-family home in Queens, where the tenants upstairs were always changing but the names on the mailbox never did, where instead of a backyard there was a long stretch of cement behind a row of attached shingle houses, and where there was no full-length mirror before the front door, Maria was never alone. Even in her bedroom, the sound soaked into and right through the walls. She was never alone when she was at home, which was why today was a special day.

“Virgins always suffer the most,” Andres said. He reached into his black Nike drawstring bag, which he carried with him everywhere. It was what he used to transport his textbooks and money and weed. That morning, on his walk to Maria’s house, he had packed it with something new. She was explicit about her instructions to stop at the pharmacy, because she knew what he kept inside his drawers at home, and she wanted a fresh one, one that wouldn’t break. She smiled now when he pulled out a condom, and with it, fell out a receipt.

Andres’s fingers were slender and long. Looking at them filled Maria with yearning. She knew Andres was concerned about physically hurting her, but this—like everything else they’d done together—would likely be fine. Above her, Maria could see the beige of the ceiling, where a fat water mark was laid over another, making an impression like Saturn’s rings. She was getting uncomfortable lying there, as if she were wearing a wet bathing suit she was itching to get out of. She helped him by rolling off her underwear and weaving her ankles out of each hole.

“Open,” Andres said, pressing onto her legs.

He pushed, and Maria felt his reach in her mind. It was as if a thousand new neurons in her brain had been activated, and her voice dimmed to make space for the others that arose. It

started with her father and brother, warning her about the evils of men. Don’t trust us, they were saying. We’re rotten. We’re liars. But those voices quickly grew tiring.

Maria looked at Andres. She wanted him to glance at her, but he seemed in deep concentration. She mimicked his solemn intensity, trying to approximate whatever he was feeling. She concentrated until she heard a different voice.

But the unit of the visit, / The encounter of the wise,— / Say, what other metre is it / Than the meeting of the eyes?

Finally, Maria laid her head back. Not her family. Not Andres.

Emerson.

Maria’s eyes were still closed when he pulled his boxers on. She thought today would be special, but now that it was over, it seemed so mundane. Sex could be happening on every school night, or in the mornings before she got on the train, and as long as nobody was around to hear it, nobody would ever know. This was an exhilarating fact as much as it was dreadful. It hadn’t been good enough to want to repeat over and over again.

“Should we go get food?” Maria asked.

Andres said nothing. He still hadn’t picked up his shirt off the floor. The morning light streaked his abdomen. He was seventeen, like her, but unlike her, he worked out every day at the gym. Every time she looked at him, she appreciated his beauty. His shoulders were like a yoke. His lower stomach narrowed into an arrow that always pointed downward.

“You move like a corpse,” he said. “And you sure you’re a virgin? You didn’t even bleed.”

Maria flinched. He was right—virgins always suffered the most. From her endless religion classes at Bell Seminary, she knew that much was true. Mary, most obviously, who watched her only son undergo the most gruesome public death. St. Agatha, whose wealthy family couldn’t save her from having her breasts chopped off before languishing in prison. And St. Lucy, whose devotion to God was so singular that she gouged out her own eyes after a suitor told her they were the loveliest shade of brown he’d ever seen. All of these virgins had suffered, but none of them had even flinched. Not like Maria had just now at the thought of being a corpse.

“I didn’t realize . . . ,” Maria said. The bow of her lip was trembling. It was still so early that she didn’t hear anyone outside. Her window faced the front of the house, and usually, on a nice Saturday in May, there was the song of children playing. By noon, the ice-cream truck would take over. But now, it was quiet. She could be noisier next time. Saints suffered in silence, but Andres didn’t know that. He wanted to be able to hear it.

“Let’s try again,” she said. “Let’s do it one more—”

The sound of a key turning ripped into Maria’s bedroom, as if it were her own doorknob being pushed.

“Hide!”

She jumped up from the bed. Andres threw her forest-green beanbag toward the door and ducked at the foot of her twin mattress. Because they shared a front door and entry hall with the people upstairs, the house resembled an apartment unit, and her parents were already in the living room just as she switched off her light. They were talking outside her closed door. Andres and Maria held their breaths.

“She’s asleep,” her mother said.

Maria strained to listen. She heard her parents’ feet make contact with the linoleum divider that separated the dining room from the living room. The kitchen was at the end of the house, and attached to it was a door that led out back. Once you were there, the hum of the refrigerator and the whir of the ceiling fan were so loud, you might not notice footsteps in the living room. They had an open floor plan, but the kitchen was in a nook to the left of the house, just behind her parents’ bedroom, and back there, it was impossible to see the front door.

“Get up,” Maria whispered.

But Andres didn’t move. She peeked over her mattress, where he had sprawled out on her gradient floor rug, striped in pink and violet. He was holding her journal open. It was a gift from a second cousin whom Maria had only met once when she visited New York from Ecuador, and the cover image was made of gold leaf and depicted a magical forest with purple mushrooms. As a girl with three piercings in her upper cartilage, who just celebrated her seventeenth birthday that March, Maria knew she had long outgrown it. Secretly, though, she wrote poems in it every night with pens that alternated between red, blue, and green tubes of ink.

Andres was staring at the last page she’d written on. She’d used looping cursive.

If love his moment overstay,

Hatred’s swift repulsions play.

“Maria, what the fuck is—”

Maria grabbed the journal out of his hands and slammed it shut. Now, she was just as angry as he must have been when he decided to call her a corpse. She thrust a finger over her lips, and he shut up. Slowly, she inched her bedroom door open. Outside, there was nobody in the living room, as she suspected, and quickly, as if she were crossing a busy street, she ushered him out of the door. When she closed it and replaced the tiny door chain, she stood there, counting. The house was at the end of the block, and by the count of ten, Andres would have descended the steps onto the curb and disappeared, anonymous, onto another street, and far out of the sight of the Rosario parents.

In the living room, she could barely hear their voices.

“It’s not an option,” her father said. “She needs to work.”

Maria moved closer. She brought down her feet toe by toe. When she had crossed the carpet into the dining room, she leaned forward and held on to the wall, making sure not to unhinge the baby photos of her and her brother, Ricky, hanging in white plastic squares. The photos were peeling away from the corners, revealing glimpses of the sample images that had come packaged with the frames. Under the dog-eared image of Maria measuring her height against an orange traffic cone was the black-and-white snout of a golden retriever.

“I agree with you,” Maria’s mother said.

“Then why don’t you take her to work with you?”

“Are you crazy? You know she would never clean.”

“She has to!”

“Shh! She’s still sleeping!” Her mother’s voice quieted so Maria could barely hear. “She doesn’t need to clean houses with me, Miguel. She can apply anywhere. She just needs her working papers.”

“Where does she get those?”

“Bell Seminary.”

It was confirmed. They were talking about Maria. Her dad had lost his job a month ago, and that same week, he had sat her down and told her to readjust her expectations about college. He suggested taking a year off to work. As if someone had taken a branding iron to her skin, Maria had started screaming.

“You know she’s going to freak out,” her mother said.

“Don’t tell her right now.”

“What are you waiting for?”

She fled to her bedroom. If she hadn’t heard him suggest it himself, she would have never believed it. Maria was supposed to be the special one—the exempted one. She’d been awarded a full scholarship at Bell Seminary, a school so elite it once was the abode of the richest man in the state of New York. She’d never told anyone about how her mother had been a maid who cleaned apartments in the same Upper East Side buildings her classmates lived in. How, recently, her mother had been forced to return to that work, and if her parents had their way, they would force Maria into it, too. She slammed the door, hoping they’d hear her. She had cried when they told her that they couldn’t afford college tuition, boulders and rivers and typhoons of tears, and now she was crying again, in just the same way.

Outside her bedroom door, Maria heard footsteps race over the linoleum. But they stopped in the living room, just short of her bedroom. They never knew what to do when Maria was having an episode of despair. In the Rosario household, where Maria always felt her parents nearby, where someone would sing a song and minutes later, Maria wouldn’t remember whose voice she was listening to, where her parents loved her so much they never quite knew how to make her understand it, Maria felt so alone.

In algebra class, they were given ass

igned seats early in the year. Maria, who got her worst grades in math, was assigned to the front of the room. Usually, she didn’t mind sitting in the front because that’s where Karen, who was the only other girl who lived in Queens, passed her perfect origami cranes made of notebook paper during class. But Maria, whose eyes were puffy and whose head felt clogged up with water, didn’t feel like sitting in the front of the room today.

“I’m sitting there,” Maria said, pointing her finger at the desk where Amanda Combs sat. Amanda was a girl who was wiry and had blond hair all over her, hair in places where it shouldn’t be. She looked like an overgrown infant. By that point, Maria knew that certain girls at Bell Seminary were intimidated by her, though she didn’t know exactly why. Sometimes, it was isolating. Other times, it was useful.

“You can’t,” Amanda said. “We’re not allowed.”

Maria clicked her tongue. It sounded the way Velcro does when it rips. It was the way her mother did it at home whenever she was annoyed. But Maria knew that girls at Bell Seminary didn’t grow up with that noise, because whenever she did it, they frowned. To them, it was a foreign sound. It gave Maria her power.

“Get up,” Maria said. “I’m giving you permission.”

Amanda stood. She went to the front and sat in the seat Maria abandoned. When class started, Mr. Willoughby noticed Maria had traded seats.

“Maria,” Mr. Willoughby said. “That’s not where I put you.”

Girls made Mr. Willoughby nervous. Maria knew this, and so did lots of her classmates. At the time he was hired, the class above Maria’s had replaced all the dry-erase markers. He went to write the “Do Now” on the board and pressed down on the whiteboard with a tampon. When the girls at Bell Seminary told this story, they always said the next part with disgust. He dropped it as if it were a severed finger. As if the tampon he was holding were used. As if he’d been holding something squirming—alive. Idiot, they’d all say, when they got to that part.

“I know, Mr. Willoughby,” Maria said, leaning over her desk. She uncrossed her legs, parted them slightly. She felt her purple bra strap fall off her shoulder. “But I’m comfortable here. See?”

They Could Have Named Her Anything

They Could Have Named Her Anything